You may be asking yourself right at this very moment, "What is 'Upanishad?'" and "How do I pronounce that strange-looking word?" and those would be good questions. The second question is simpler, so let's start with that. If you were to ask google translate how to pronounce it with a Spanish accent, it would sound a little like oo-PAWN-ee-Shawd.

This little exercise we just did, in itself, was interesting - just because the name is written doesn't mean I know how to communicate how it sounds to you without depending on our oral skills.

This is my attempt at recitation

This video is a recording of my recitation of part of one of the Upanishads, which can be found in Michael Nagler's translation of ancient Hindu scripture. Through reading some of the Upanishads, I learned that this ancient Aryan civilization believed wealth would not lead to happiness, and that eternal happiness comes through recognizing that we are all part of a Self. As Yajnavalkya tells his wife, Maitreyi, in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, "Everything is loved not for its own sake, but because the Self lives in it."

|

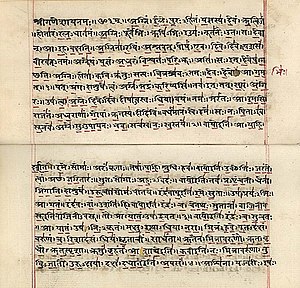

| A page of the Upanishad, written in Sanskrit |

Now to the first question. The Upanishads was a series of spiritual teaching sessions and oral Indo-European Sanskrit poetry that spanned 1000 BC to 200 BC found in what is now modern-day India. "Upanishad" in Sanskrit literally means "sitting down near," (The Upanishads, 19). Teachers who had found a higher spirituality through meditation, concentrating on their inner-selves, would retreat to ashrams, "forest academies," and students would join them there, sitting at their feet. They would ask them life questions, really desiring to know the answers, and observe how they lived. This took place along the upper Ganges river.

|

| Maharishi Mahesh Yogi ashram |

Doesn't that look awesome! I feel like I could probably remember a lot if I got to live in an elevated hut. Okay. Onward. Before this time, the inhabitants of the Indus River Valley had a highly advanced civilization that included a written language and worship of fertility gods. When they were invaded by the Aryans, an Indo-European race with superior military technology and solely an oral language, these two cultures combined to make up modern-day India.

|

| A view of the Ganges River at sunset |

|

| Walter J. Ong, author of "Orality and Literacy" |

What makes this idea of conversation and oral poetry written down is this insight into mnemonics in Walter J. Ong's book on "Orality and Literacy" suggested by Dr. Petersen. He asks, "Did oral singers actually shift the formulas, so that individual metrically regular renditions of the same story differed in wording? Or was the story mastered verbatim, so that it was rendered the same at every performance? (Orality and Literacy, 59)." It wasn't as if people were going to check every time that a poet, or a brahmin, as in the Aryan civilization, was using the exact same words.

Reciting verbatim might not have even been their goal. In fact, Ong tells us that after a study of present-day illiterate Yugoslavian bards, "the memory feats of these oral bards are remarkable, but they are unlike those associated with memorization of texts" (60).

|

|

Yugoslavian bards would often postpone performing a poem until a day or so after they had first heard it (see maps above for overlap of Greek and Yugoslavic civilization). They would take this time to internalize its message. Then, using the same rhythm and metrical pattern, but alternating the words slightly, they would fit them into a structured meter on the spot, as Summer talks about in her post.

Which brings us back to this Aryan civilization. If we're looking at only a verbal Indo-European sanskrit, we need to keep in mind that we are viewing it as a civilization with a written language. "...An entirely oral language which has a term for speech in general... [may] have no ready term for a 'word' as an isolated item, a 'bit' of speech, as in "The last sentence here consists of twenty-six words.' Or does it? If you cannot write, is 'text-based' one word or two?" (Orality and Literacy, 61).

Reciting exactly the same conversations and poetry as one's teacher, along the bank of the Ganges, would have interfered with the message being conveyed - that a higher consciousness of the world and of ourselves needs to be reached to find inner-peace and joy. In trying to remember the exact words of their own teacher, a former student would lose the opportunity to teach you cool things like Master Shifu, which is why I've provided this video of his successful understanding inner-peace.

This was a really cool post. I had always imagined bards tirelessly memorizing exact words of poems and songs, but it makes sense that they would internalize the message and recite the general meaning of it with their own twists. This relates to what I was saying about Einstein. He internalized and learned how formulas worked and their purposes without remembering the exact formulas. I think this is the best form of learning. It's more valuable to us to know the teachings of Jesus and the meaning of his message rather than memorizing passages of scripture verbatum.

ReplyDeleteI think Rachel brings up an interesting point about the spontaneity of the oral performances. It seems that they may have memorized these stories verbatim, but as we discussed in class, there is a great deal of tapering the story to fit the audience like in Beowulf. This would require a great deal more of improvisation like Ong remarks.

ReplyDeleteAlso, the comparison of mnemonics and oral traditions across cultures is a good connection to make. The forums of the Aryans and the Yugoslavians might have been different, but their purposes to spread knowledge and stories are similar in cause.

It really puts memorizing in a new light. Its like jazz improvisation where you memorize the general chord progressions, but not necessarily the song note for note. The creativity effect really adds to the emotion of a poem or piece of music.

ReplyDeleteKind of makes me question why we give awards out to elementary school students who can memorize things like the Gettysburg address and Preamble to the Bill of Rights.

Wait! Thanks for these comments, guys. But I like memorizing verbatim stuff too! Those were some beautiful words in the Gettysburg Address, and although an elementary school kid might understand Abraham Lincoln's general meaning and could say, "People died here, but let's make sure it wasn't for nothing," is a lot less powerful than his words that inspired the North during a really, really hard time. I think there is also value in remembering beautiful things - not so exactly that you criticize others for being a little off on them, but really tasting those words and enjoying them and pondering. Anyway.

ReplyDeleteOk, fair point memorizing helps connect with the beauty of the spoken word. I'll admit that. But honestly, there is still no practicality with memorization. Maybe we feel inspired for one fleeting second, but its our own choices and actions that change the world, not the spoken word. I'm sure Lincoln didn't have his Gettysburg address memorized when he inspired the North.

ReplyDeleteAnyways that's my opinion, memorizing verbatim is not practical.Words don't accomplish nearly as much as actions.