When I did my research for oral

knowledge in ancient Greece, I checked out a big stack of books. When I got

home, I dismissed the book Voice Into Text: Orality and Literacy in Ancient

Greece because it didn’t deal strictly with oral culture. But with the admonition

to participate in self-directed learning, I decided to explore. I soon found a

pertinent chapter entitled “Greek Oratory and the Oral/Literate Division” by

Ian Worthington. It discussed the transition from a mainly oral society into a

mainly text-based society, and the importance behind these mediums. Sound

familiar?

Well

it should because it basically embodied the essence of what we have been

talking about in class, and the article puts it in the context of ancient Greek

culture. As I discuss the transition from orality to text and its effects, I

will focus on two main questions:

What effect did the

change from oral speech to written speech have on the substance of speeches we

have today? How does this change affect the veracity of speeches as historical

source material?

To answer these questions, we must

identify two main types of orality: oratory, used in the presence of a case of

a law court or Assembly, and poetry, which includes stories, dramas, and songs.

Oratory, as we can understand it, has

a relatively short life. It is no longer applicable after its first

performance, so it can be said that the complexity of the ring composition (see earlier post) and stylistic symmetry found in these speeches is lost on a

listening audience, who hears it only once and often with distractions. So when

these are revised after oral delivery, they are directed toward a non-listening

audience, one with more time to ponder and appreciate the subtleties. (Like

Professor Burton pointed out in class, Walter Ong saw this as the analytic

aspect of literacy.)

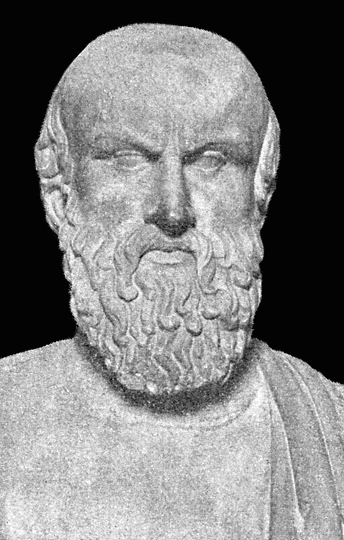

|

| Aeschylus, ancient Greek tragedian |

Poetry on the other hand, counters

this claim. Homer employed a very complex composition, which was not lost on

its listeners. Also, Aeschylus’ Greek, an example of tragedy, included even

more complexity and density, and its message was successfully communicated

through this medium. But the difference here is that oratory, as compared with

Homer and Aeschylus, has a short shelf life, whereas poetry is meant to be

heard, recited, and performed over and over again.

So the purpose of ring composition

in oratory is to keep listeners attentive and to repeat key points for

listeners who may be distracted by physical surroundings. A speech’s complexity

in structure and repetition also signifies a “reader/writer process”, which is

native to oral tradition but has been more associated with the growing

communication through writing. So then why is it used in poetry? Worthington posited

“Like Homer, from original oral beginnings or oral style a speech, containing a

mass of differing items of information, each linked to each other and

intimately related to the entire framework of the speech, has become shaped and

changed in structure and format in its revision stage (by the impact of

literacy).” And thus he proves that complicated ring composition or symmetry is

evidence of a literate poet just as the complexity of oratory denoted a

literate author.

To answer the second question,

Worthington emphasizes the use of speeches by historians to be the information

imparted on history and society, but what about the post-oral use of speeches

in classical Athens? What role did the revised speech play if it did not end up

as part of rhetorical curricula, as many did not? The answer revolves around

the use of the revised speech to testify of the orator’s own reputation,

allowing him to show off his rhetorical skills to the growing wave of literate

communicators, and use perfect medium to advertise and promote business.

Next we come to this question: What

effect did literacy have on society? I remember the phrase “Knowledge is Power”

on a poster in my 3rd grade class, and the same principle applies

here. The literate in society had a power over the illiterate. It is these few

literate in ancient Greek society who would attend the symposia and discuss the

topics brought up there, which were philosophical and political. With this

power, people like Aristophanes feared that the literate had to the power to

“beguile the people and assure their political ascendancy by exploitation of

rhetoric and law.”

And so I’ll turn the tables on us

now. Is it true that the literate have power over the illiterate? Is this used

justly or unjustly? In regards to the transition from oral to textual, how are

our speeches and poetry the consequence of our literate society? What has been

lost or gained from this transition?

I think this post has a lot to do with what Andrew was talking about in his post about Ancient Greek civilization, as well as the link to Rhetorical study in Ancient Greece. It's interesting that people often dismiss learning how to write well, as in English, as an important part of an education, when we see so much evidence that it is really powerful and important to be able to express your ideas well. As the author of that "Gorgias' Encomium of Helen" showed, Gorgias was able to provide a convincing argument to the innocence of Helen, launching-hundred-ships style, just by using rhetorical strategies, just for the fun of it! It was completely contrary to the dominate idea in ancient Greece of Helen's blame for the beginning of the Trojan War, a really powerful argument, and he was just using these strategies for fun. Craziness.

ReplyDeleteInteresting question: do the literate have more power? I don't think power is the right word. I'd say those who can read have more opportunities to grow and gain knowledge. Once you can read, you gain access to this entire web of information and knowledge simply at the tip of your fingers.

ReplyDelete