|

| Talipot Palm tree |

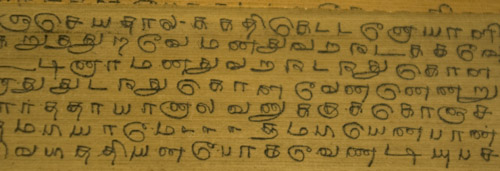

This is almost

exactly what our Indian-influenced artefact looks like, although admittedly ours had fewer leaves. For our civilization group, we decided to use the medium of talipot palm leaves and a reed pen to cut into the surface, as the Aryans began doing during the Age of Sutra. You can read more about their writing techniques in

a prior blog post.

The talipot palm leaves were used to write on until the age of print, when the recopying of deteriorating palm leaves became impractical. The picture on top looks like an artefact shown during our time in Special Collections in the library. The leaves were often connected by string through one or two holes, and book-ended by wooden, ivory, or other hard panels, either plain or adorned.

After we had decided on our materials and what we wanted to write about (to be revealed when a group translates it), I once again realized what Summer pointed out in

her recent post: "it's all about the process" with this civilization class. It is ALL about the process.

|

| dried Bamboo leaf |

I pondered this morning and yesterday over what I could bring to our 4 o'clock meeting today in the Wilkinson Center that would be a plausible writing material for the Aryans. After many google searches, I discovered that talipot palm leaves are probably not sold locally and would not be shipped in time, and that the cheapest palm trees I could find were over $40.

Sister Sarah,

the rockstar that she is, brought me to a Asian grocery store in Provo and the man at the counter immediately brought us to the back where there were dried bamboo leaves! the same size I'd researched talipot palm leaves were and from around the same geographical region.

|

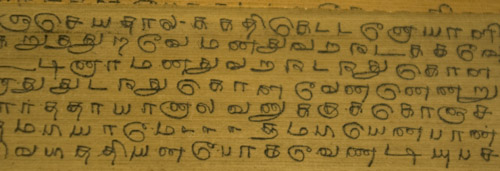

| an example of a palm leaf manuscript |

Back at the Wilkinson Center, Jacob, Lauren, Crista and I met at a large round table with our supplies, which included twine, dried bamboo leaves, India ink and paintbrush, a wood-like panel from the Bookstore, a hole puncher, and a white plastic knife. An hour later, after much copying and re-copying, cutting and splicing out the rib down the center of the leaves, we had a leaf about eight to ten inches long with an ancient Indian language written on it, and a small blank manuscript tied through by two pieces of twine and protected between two panels of wood. Jacob graciously volunteered to go outside and cover the wood in mud for a more authentic look, and the end result was AWESOME.

What surprised me most of all was how difficult it was to recopy our chosen language onto our medium. Not being familiar with the language, it felt like we were drawing pictures instead of writing actual words, in the hope that we were copying the symbols correctly. It reminded me of Doctor Petersen's lecture on the benefits of having the illiterate copy text, that they just wrote what they saw and didn't try to add anything in. In this case,

we were the illiterate.

|

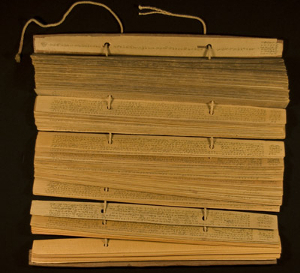

| deteriorating talipot palm leaves |

Lastly, I can't imagine having to string more than the three leaves together that we did, meticulously putting the string through each hole, leaving space for writing to happen on the sheets. Many sheets were gilded, but these leaves are not the kind of stuff that lasts. They are sturdier than one would expect, but deterioration really did mean the sacred texts and other writings on them needed to be transferred every three to four centuries. That is a lot of work to preserve the texts that we now have from Ancient Indian civilization. I raise my imaginary hat to those scribes.

You can read more about talipot palm leaf manuscripts

here and

here.

I think the expression you were looking for was "tip my cap"... haha! It's interesting how much the medium affects the message. My group's was much shorter than the group's we got to translate, because we had to chisel ours in stone while they had to write their's on balsa wood. It's a lot easier to type a blog post than it is to engrave one in stone.

ReplyDelete